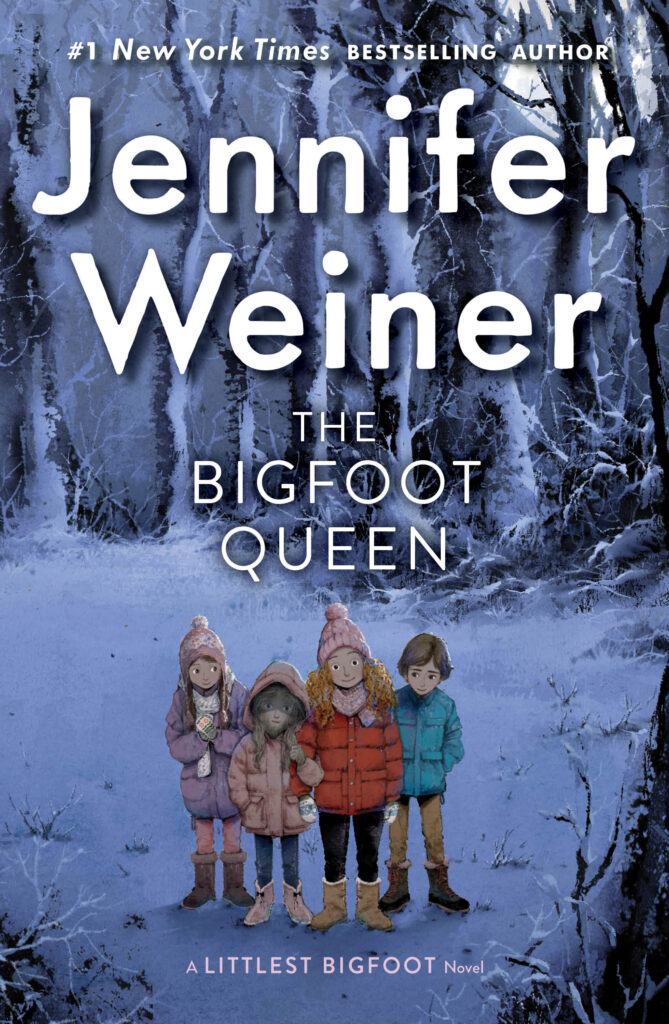

Exploring Feelings and Facing Challenges, a cover reveal, guest post, and excerpt by Jennifer Weiner

Jacket illustration (c) 2023 by Ji-Hyuk Kim

Once upon a time, long, long ago, in a small town in Connecticut, there lived a doctor and a teacher, in a house full of books. Every night, the four children would gather in their parents’ big bed, and the father would read to them.

My father was a complicated, troubled man. But that one thing, he did right. He read poetry, from a book called “A Child’s Garden of Verses.” He read us age-appropriate versions of the Aeneid and the Odyssey, and “A Child’s History of the World.” But the book I remember most vividly was the edition of Grimm’s Fairytales my father had, which were lavishly, graphically illustrated in full color plates. To this day, I can recall the pictures of Cinderella’s stepsisters, mutilated feet dripping blood while birds pecked out their eyes…or Bluebird’s wife, gazing at the decapitated corpses of her predecessors as they hung in a row on the dungeon wall…or Rumpelstiltskin, capering around the fire, all but salivating at the prospect of forcing the miller’s daughter to give him her baby.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

I think about that book and those pictures a lot, as I consider the current wave of book bans and censorship sweeping across the country.

As an author, as a reader, as a supporter of the LGBTQ community, and of anyone who’s ever felt different, I abhor the efforts to remove books for the supposed sins of featuring gay or transgender characters or content. I’m a little more sympathetic to the sensitivity readers hired by Roald Dahl’s publishers to remove offensive or outdated language from his beloved stories. And, as far as the people who don’t want children learning the true history of slavery or the Holocaust because they might feel ashamed or guilty when they discover how people who looked, or believed, like they did, treated people who looked, or believed, differently, I’d say two things. First, that those who don’t understand history—real history, not some bowdlerized, sanitized version—are condemned to repeat it. And, less seriously, do they know how hard it can be to make kids feel guilty or ashamed about their own actions, let alone what white Americans did to enslaved Black Americans years ago, or what Adolf Hitler’s supporters did to Jews in the 1940s?

Kids are resilient. They are stronger than we think. They can handle the truth about what really happened in the past. They can handle reading about people who are different than they are … and no one is served when trying to hide it, or to pretend we’re all the same.

But, even as I roll my eyes at the parents who think that removing books about school shootings or sex from school libraries will accomplish anything besides making kids frantic to read them, or who believe that kids shouldn’t learn history because they’ll feel guilty if they do, I can try to be generous, and tell myself that they are well-intentioned parents. The ones who aren’t doing it to score political points or foment culture wars as a distraction from the real issues – are responding to the same motivation: These books, these characters, represent something that scares them, something they perceive as a threat, and they want to keep kids safe.

But here’s the thing. Parents can pull books from the libraries. They can’t erase headlines from the newspapers. They can limit and curtail the imaginary realms their kids explore, but they can’t affect the reality in which their kids live. Parents can take books about school shootings off the shelves…but what do those parents do when an actual school shooting occurs? Or when active-shooter drills as part of the curriculum? What do they say when their kids read about a 16-year-old Black boy who was shot for ringing the wrong doorbell, or a six-year-old who brought his mother’s gun to school and shot his teacher, and it’s fact, not fiction?

Kids live in a violent reality. They live in a diverse world. And books have always been where they’ve gone to explore danger and difference, knowing that it’s all make believe, that many stories end with “happily ever after,” and that they can close the covers if it’s ever too much. A safe space, if you will.

When I wrote my “Littlest Bigfoot” trilogy, I didn’t shy away from the hard parts. One of my main characters, Alice, is cruelly bullied in the first book. Her classmates make fun of her. Even worse, her own mother, thin and chic, disdains her, not knowing what to make of her sturdy, wild-haired daughter. The kids behave badly. The grownups are even worse. And, even though there are heroic adults; even though the bully and her victim eventually become friends, even though we learn that Alice’s mother doesn’t really hate her, even though everyone works together and there’s a happy ending, I suspect that, just like my most vivid memories from Grimm’s Fairy Tales are the blood and the horror, what kids might remember best from my books are the sad, scary parts: Alice, alone and friendless. Millie, a misunderstood outcast. Jeremy, ignored by his parents, disbelieved by his classmates and teachers. Jessica, desperate to hide her physical differences, because she’ll surely be toppled from her spot at the top of the pecking order if her friends find out.

As a mother, I understand the impulse to swaddle our kids in bubble wrap; to go out ahead of them into the world and clear away every obstacle, to do everything I can to keep anything from harming them. As a pragmatist, I understand how futile that would be. As an author, I believe that books are, and have always been the best places for kids to confront the things that scare them or challenge them, and to know that, however monstrous or misunderstood they feel, they are not alone.

And now, an excerpt from The Bigfoot Queen

CHAPTER 1

Charlotte

CHARLOTTE HUGHES HAD BEEN BORN IN A dying town, to parents who didn’t survive to see her second birthday. They’d perished in a car accident, after their minivan had hit a patch of black ice and skidded off the road. Charlotte’s father had been pronounced dead on the scene. Her mother had died in the hospital, later that night. Baby Charlotte, strapped into her car seat, had survived without a scratch, and had been sent to live with her father’s mother, her only surviving relative, who, clearly, had no interest in raising another child. Grandma managed Upland’s only bed-and-breakfast, and it was an exhausting, thankless job—but one Grandma always said she was lucky to have, given how many in town couldn’t find any work at all.

In the winter, when the skiers who couldn’t find lodging closer to the mountain resorts booked rooms, Grandma worked from sunrise to late at night, doing laundry, cleaning, and cooking, and as soon as Charlotte was tall enough to push a broom or carry a load of dirty towels to the basement, she had to help her. There were floors to be swept and mopped, beds to be stripped and made, trash cans to be emptied, carpets to be vacuumed, and toilets to be scrubbed. Even when they didn’t have guests, there was always cleaning. The big, old house seemed to generate its own dust and grow its own cobwebs. Little Charlotte would wake up at five in the morning to iron napkins and to bake scones and clear snow off the porch. She made beds and cleaned bathrooms. She learned to be invisible, to slip in and out of the rooms when the guests were gone, so quickly that they hardly noticed she was there. Her hands would chap and her skin would crack and she’d yawn her way through her school days.

And, all around her, Upland was dying.

When Grandma Hughes was a girl, Upland had been a thriving town, with a ski resort and two different fabric mills that stained the river with whatever dyes they were using that week: indigo, crimson, goldenrod yellow, or pine-tree green.

Then one of the mills had caught fire, and the other mill had closed, and the Great Depression and the two World Wars had come.

Young men had gone off to fight and hadn’t returned; families packed up and moved to more prosperous communities. In 1965, the interstate highway, which went nowhere near Upland, was completed. Skiers used it to travel to the mountains that were close to the highway, and Upland was not. Two years after the interstate opened, Mount Upland was closed.

For as long as Charlotte could remember, her hometown had been full of run-down houses and rusty trailers, roads with more potholes than asphalt, where the schools were ancient and the bridges were elderly and every third storefront had a faded “GOING OUT OF BUSINESS” or “EVERYTHING MUST GO” sign hung over its soap- covered windows. Every year, more and more people moved away, to bigger towns with better opportunities.

Then, when Charlotte was twelve, Christopher Jarvis had come to town.

Famous Scientist to Establish New Labs in Upland, read the headline in the newspaper Charlotte saw on her grandmother’s desk. Famed scientist Christopher Jarvis, owner of Jarvis Industries, which holds patents on everything from dental tools to heartburn medications, is opening a new research and development facility in Upland. A spokesman for Dr. Jarvis said the renowned scientist and inventor has purchased the eighty acres of land that were formerly Ellenloe Farms, and plans to break ground on the labs next month, with an eye toward opening next year. “We’ll need everything from support staff, such as custodians and cooks, to researchers and security personnel,” a spokeswoman for Jarvis Industries said.

“Maybe we’ll get some more guests,” Grandma had said, not looking especially hopeful. She spooned a clump of macaroni and cheese onto Charlotte’s plate, where it landed with a dispirited plop. Charlotte tried not to sigh. She couldn’t remember her parents, not even a little bit, but somehow she thought that if her mother had survived, she’d buy name-brand mac and cheese, not the generic kind, and she’d make the sauce with milk instead of water.

The next day, the school was buzzing with the news. Courtney Miller said her mom had already applied for a job as an administrative assistant, and Lisa Farley said her mom had gotten a call about working in the cafeteria. Ross Richardson said his dad had heard there was going to be a job fair at the community center, and Mrs. McTeague, who taught English literature, said she’d heard that the lab would bring more than five hundred new jobs to Upland.

Charlotte took the long way home after school, wondering whether her grandmother would ever go to work for Jarvis Industries. Maybe they could sell the inn and move to a regular house, where they didn’t have to sleep in cramped bedrooms in the attic and worry about being quiet so the sound of their feet or their voices wouldn’t disturb their guests. Charlotte would be able to get a job babysitting, or she could be a lifeguard in the summertime, instead of making beds and scrubbing toilets for no money, not even an allowance. She could get an iPhone, instead of the crummy knockoff with limited data that was all her grandmother could afford, and a pair of the clogs that all the girls were wearing that year. She could get new clothes and concert tickets and a car when she was old enough to drive. Maybe her grandmother wouldn’t have to work so hard, and maybe she’d stop being so grumpy with Charlotte when she wasn’t so exhausted, with her back and her knees hurting her all the time. Maybe everything would change.

When Charlotte arrived at the inn that afternoon, she saw a shiny black car in the driveway, and a man in a suit and shoes as shiny and black as the car, standing on the front porch. “I hope you’ll give our offer some serious thought,” he said to Grandma Hughes, who didn’t answer. The man shrugged, climbing into the car and giving Charlotte a quick, two-fingered salute before driving away.

Charlotte could tell from her grandmother’s tight-lipped expression that asking questions would only cause trouble, but she couldn’t keep quiet. “Who was that man?” Charlotte asked, taking her place in front of the kitchen sink to start on the afternoon’s dishes. “What’d he want?” “He’s from the Jarvis company. They want to buy the place,” her grandmother said. She’d pulled a bunch of celery out of the refrigerator and was going at it with a cleaver as if she was imagining it was the Jarvis representative’s head.

“And you won’t sell?” Charlotte asked. Her heart was sinking.

“This place belonged to my parents. And my father’s parents before them,” said her grandmother. “It should have gone to my son. It’ll be yours someday, I imagine.”

I don’t want it, thought Charlotte. “Wouldn’t it be easier, just to sell it? You could probably retire!”

“Easier doesn’t always mean better.” Her grandmother kept chopping, dicing the celery into tinier and tinier pieces. After a minute she muttered, “And it’s dirty money.”

“What do you mean?”

“I’ve learned a few things about Jarvis Industries.” Chop, chop, chop, went the heavy silver blade. “All those pharmaceutical companies are bad news. Profiting off people’s illnesses. Making their pills so expensive that regular people can’t afford them. Getting rich, while sick people suffer and go without to afford their medication. Dirty money.”

Charlotte decided she didn’t care if Jarvis Industries’ money was dirty or clean. If they’d offered it to her, she’d have taken it, and if Charlotte inherited the inn and the Jarvis people still wanted it, she would sell it to them and never look back.

Her grandmother pressed her lips together, even more tightly. “I’ve heard other things too,” she said.

Meet the author

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

Jennifer Weiner is the #1 New York Times bestselling author of nineteen books, including That Summer, Big Summer, Mrs. Everything, In Her Shoes, Good in Bed, and a memoir in essays, Hungry Heart. She has appeared on many national television programs, including Today and Good Morning America, and her work has been published in The Wall Street Journal and The New York Times, among other newspapers and magazines. Jennifer lives with her family in Philadelphia. Visit her online at JenniferWeiner.com.

About The Bigfoot Queen

From #1 New York Times bestselling author Jennifer Weiner comes the third and final book in the “cheerful” (The New York Times Book Review) and “charming” (People) trilogy about friendship, adventure, and celebrating your true self.

Alice Mayfair, Millie Maximus, Jessica Jarvis, and Jeremy Bigelow face their biggest challenge yet when exposure of the sacred, secret world is threatened by a determined foe, someone with a very personal reason to want revenge against the creatures who call themselves the Yare.

The fate of the tribe and its members’ right to live out peacefully in the open is at stake. Impossible decisions are made, friendships are threatened, secrets are revealed, and tremendous courage is required. Alice, her friends, and her frenemies will have to work together and be stronger, smarter, and more accepting than they’ve ever been.

But can some betrayals ever be forgiven?

ISBN-13: 9781481470803

Publisher: Aladdin

Publication date: 10/24/2023

Series: Littlest Bigfoot Series #3

Age Range: 8 – 12 Years

Filed under: Guest Post

About Amanda MacGregor

Amanda MacGregor works in an elementary library, loves dogs, and can be found on Twitter @CiteSomething.

ADVERTISEMENT

ADVERTISEMENT

SLJ Blog Network

Coming Soon: The Top 10 Posts of 2024

31 Days, 31 Lists: 2024 Science Fiction Books for Kids

Exclusive: Papercutz to Publish Mike Kunkel’s Herobear | News and Preview

The Seven Bills That Will Safeguard the Future of School Librarianship

ADVERTISEMENT

Really appreciated Weiner’s thoughts here, and I totally agree with her. I love that she gives grace to parents who think that they’re acting to keep their kids “safe” while not endorsing their actions. Banning is never the answer, and it will inevitably do more harm than good.